If you play the harmonica, or have a love of Country music, there’s a good chance you know who Charlie McCoy is.

Charlie’s take on Georgia On My Mind recorded during the Jerry Reed Guitar-Man Tribute in 2014:

Maybe you have one, or more likely some of his forty-three albums, seen him on the Grand Ole Opry, in concert, or festival, or remember him from his days on TV’s long-running variety show, Hee Haw.

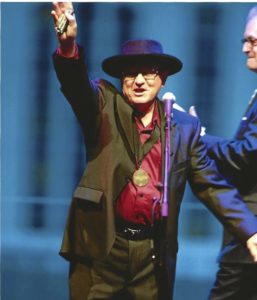

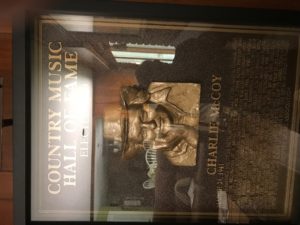

Maybe you watched as he received his Grammy, 2 CMA awards or 7 ACM awards, or when he was inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame, the Country Music Hall of Fame or the International Musicians’ Hall of Fame.

Maybe you’ve tried to play, even mastered his best-selling version of Orange Blossom Special, which is no easy fete.

Maybe you think you know a lot about Charlie McCoy, but between the lines and headlines there are a bunch of untold stories. Memories and opportunities behind the accolades that define him and continue to spur him on.

Charlie was born in Oak Hill, West Virginia, but it was a short stay. When his parents divorced, he was all of two years old. Then saw his dad moving to Florida, while Charlie and his mom remained in the area, eventually moving just six miles north to Fayetteville─the big city and the county seat where Mrs. McCoy had taken a job as a legal secretary.

Charlie says he was a sickly child, and after a particularly rough bout of anemia, it was decided that he would spend the school year with his dad, thus avoiding the harsh West Virginia weather, and the warm and welcoming summers with his mom back in Fayetteville.

Like many boys his age, Charlie spent a fair amount of his free time with his head buried in a comic book. It was there that he came across an ad with an eye-catching line that read something like this: “You Can Play the Harmonica in Seven Days or Your Money Back.”

Wow!

The cost: Just fifty cents and a box top. Charlie asked his mom if she would stake him for the fifty cents. “She was a single mom,” he says, “and this was at a time when you could buy something with fifty cents. But she came up with the money, and let me buy it.”

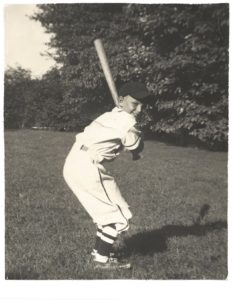

Did the promise live up to its billing? Well, says Charlie, “It was summer, and we were all interested in baseball, and so I didn’t seriously delve into it much.” But he says, he quickly realized that he had a better-than-average ear, and in short order (if not the promised seven days) had learned how to play a couple of Steven Foster tunes and “My Country ‘Tis of Thee”.

When summer came to an end, and with school about to start, Charlie returned to Florida, harmonica in tow. What happened next surprised him. It was a nice surprise.

“When my dad unpacked my suitcase he saw the harmonica and he looked up at me and said, ‘Where did you get this?’ And he picked it up and played a song on it: a simple tune called Home Sweet Home. I didn’t know he could play,” says Charlie, “so I thought that was pretty cool.”

As it turns out, his dad’s repertoire was just about as wide as Charlie’s. “He could play three songs” recalls McCoy. But there was a connection. A family history of sorts. Again, a nice surprise.

But if that moment in time struck a chord, the harmonica would once again take a back seat to something else. This time, it was the guitar, a Christmas present from his dad.

“And that was my focus for many years. I didn’t get serious about the harp until I was sixteen and heard a record by Jimmy Reed.” What song? Charlie says it was probably “You Got Me Dizzy” or one of Reed’s other minor hits.

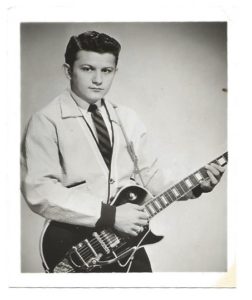

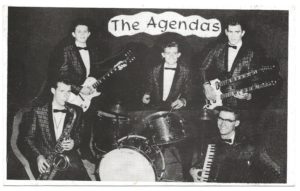

By the time he reached his teens, Charlie had put together a rock and roll band. “We did Elvis, Carl Perkins and Fats Domino songs” he says, “and there was a little record label by the name of Agenda that got interested in us.”

Agenda’s owner promised the boys a contract, the only catch: they had to change the band’s name to include the name of the label. Charlie was willing, but “Charlie McCoy and the Agendas” never made it to the studio, which, according to Charlie, turned out to be a good thing. “My dad didn’t trust the guy,” he explains, “and wouldn’t let us sign the contract. The guy turned out to be a crook, so my dad was smart about that.”

Despite this momentary setback, the band rocked on, playing local dances for peanuts. “We didn’t play much,” he says, “but we had a good time.”

But in the summer of 1958, with his record debut cut short, Charlie decided it would be best to set his rock and roll dreams aside and go to college, where he would major in Music Education. As his music teachers considered his chances of making the grade, they came to the conclusion that he needed to play something other than the guitar or harmonica if he was going to be accepted into the program.

“They figured that the easiest thing I could learn was the (stand up) bass,” he recalls, and following their advice, he started taking lessons, and spent the next two summers practicing what he had learned on a borrowed bass.

If practice didn’t make perfect, it did earn him a spot in the school orchestra, albeit as third chair. Says Charlie, “As long as the parts were easy, I was okay.”

But playing the bass didn’t come naturally, and coming up with a way to relate to the instrument took a bit of ingenuity. He laughs as he recalls the way he got around the problem. “I took a pencil and drew fret marks on it” Why? “… because I didn’t know what I was doing.”

But not to fret, his goal was not to be the world’s greatest bass player; it was to get accepted into the University of Miami’s music program. At the end of his junior year he happened to see a note posted on his high school bulletin board. Come September, the school would be offering a brand new Music Theory course.

Any questions as to whether Charlie was up to the challenge were dispelled when he read the line under the announcement: “Anyone who knows where Middle “C” is on the piano goes into the advanced class.” Charlie was intrigued.

“So I signed up,” he says, “and I must say I loved the class, I was like a sponge; I took it all in, and I really understood it. But my one problem was that my penmanship was terrible, and at the end of the year the teacher said “I know you really get this, but the way you write, no one will ever know it.” He laughs.

It turns out that the class was an experiment, with his high school being the only school in the state to offer such a program. His orchestra teacher –one of the two teachers who had encouraged him to play the bass, taught the class. It would give him a leg up – not only in college, but the music business.

But at eighteen, with his band having disbanded, Charlie’s plans didn’t go any further than getting into the University of Florida.

Weekends were spent making music at The Old South Jamboree, a local country music dance hosted by a fellow named Happy Harold. “My job was to play rock and roll for ten minutes every hour” says Charlie. Not exactly the Grand Ole Opry, but a start.

CHARLIE PLAYING A MEL TILLIS TUNE: HEART OVER MIND…

And then─a break, when singer/songwriter Mel Tillis happened into the place while Charlie was on stage. McCoy remembers the way it all came down. “So I’m playing this country music dance, and one night Mel Tillis comes in. I think he probably had a couple of beers. And he came up to me and said, ‘Son, you come to Nashville, and I’ll get you on records tomorrow.’” And with that, Tillis, who spent a good bit of time in Nashville writing for Cedarwood Publishing, gave him the number of his manager and publisher, future Country Music Hall of Famer, Jim Denny.

Charlie was pumped.

Setting the scene Charlie takes it from there: “The day after graduation, Happy Harold drives me to Nashville. And we go to Jim Denny’s office to meet with Mel. But the receptionist says, ‘Sorry, Mel’s out of town.’” Charlie laughs as he recalls thinking, ‘Well, thanks a lot. We just drove nine hundred miles…’.

And then… and then she said four magic words that would change the course of Charlie McCoy’s life: “but Mr. Denny’s’ here.”

“So we went in, and I told him my name. And he said, ‘Mel told me about you.’

‘Really?’

“And he said, ‘You want to get some auditions?’

“‘Yes sir.’

“So he took me to Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley, and I played and sang ‘Johnny B Good’. And to be honest, I didn’t know who these people were. And Atkins said, “Son, I think you’re pretty good, but we’re just not doin’ that kind of music here.’ And I thought, ‘What do these country bumpkins know?’”

Owen Bradley’s reaction? Says Charlie, “Same thing.”

“So I’m really down now; I made the trip for nothing. And then, Bradley says “I’m having a session this afternoon, you wanna come watch?

Go to a session? Sure!

“So I go back to the studio, and at one end of the room there was a stairway. And he said, ‘If you’ll sit halfway up that stairway, you’ll get a real good idea of what we do here.’”

Charlie says he looked around at the sea of faces. He was eighteen at the time, and admits that he was pretty cocky. “I thought I knew everything”, he says. “And I looked at these old guys and I notice that there are no music stands. And I’m thinking, ‘Where are the music stands?’ And then the artist comes in: thirteen year-old Brenda Lee. And I’m thinking, ‘My God, this is just a kid. Who would want to record a kid?’

“So I’m up there on this perch, and they start playing this song, and it looked like none of the musicians were paying attention. They’re making funny jokes. But when the red light came on, they started to play, and that first playback was so good. And at that moment I thought, ‘I don’t want to sing; I want to do this.’ I wanted to be a studio musician.’

“The next day, we were about to leave when Denny said ‘There’s another session with the Jordanaires.”

Charlie says that while he was aware of the group’s back-up work for Elvis, he didn’t know that they were doing sessions with many Nashville artists on a regular basis.” Anxious to sit in on another session, he made his way over to the studio to see what he could see.

“And that‘s when I saw music arranger Neal Matthews Jr.. And they introduced me to him. And unlike the Brenda Lee session he did have a music stand─ with a yellow tablet with a bunch of numbers on it. And I’m looking at it, and he said, ‘Do you know what this is?’ and I said, ‘I think I do.’ And it was a shorthand music notation that was taken from classical music, but simplified in a way that it became logical and easy to understand.”

Eventually says Charlie, “that became what is known as the Nashville Number System,’ a sort of shorthand for people who don’t read music.

“It was so logical. I had been studying Classical harmony in high school, and compared to the number system, it looked like trigonometry.

Charlie returned to Florida “all fired up” and ready to take on the world, or at least college. His bass lessons had paid off, even though he admits that he could barely play. That opinion was confirmed by his college instructor, who, after hearing Charlie play said, ‘Oh my gosh; I want you to forget what you don’t know, and start over.”

Charlie minored in ─and did a got bit better on the piano, thanks again to his good ear, great memory, and that music theory class he had taken back in high school.

He was a college man now, and should have been looking forward to a career in music education. But after his trip to Nashville, he was smitten, and as time went on he found himself thinking more and more about the possibility of becoming a session musician.

Happily, before the year was over, fate smiled upon Charlie, when a Nashville friend called to say that if he could get there post haste, there was a job waiting for him playing the guitar with a singer named Johnny Ferguson.

Charlie didn’t think twice, and left for Nashville as soon as he was able, dropping out of college, and, he says, breaking his father’s heart. Did his dad ever forgive him? What do you think? “He forgave me [much later] when I introduced him to Dolly Parton.” You can hear the smile in his voice.

Once in Nashville, as with his first visit, things didn’t quite go as expected. “I got there, and went to the rehearsal, and Ferguson said, “Well, I never heard back from you. I’ve already hired a guitar player.”

Oh boy. But this was a nice man, a man who realized what this meant to the now ex-college student, “and he said, ‘What else do you play?’ And I said, ‘I play the harmonica.’ And he said, ‘Do you play drums?’ And I thought to myself, ‘Say ‘no’, and you’re done.’ So I said, ‘Yes’, I can play, but I don’t have any’, and he said, ‘We’ll get you some.’

“So my first gig was playing drums with Johnny Ferguson in a Toronto hotel lounge. And I was happy making music and seeing Canada. It was cool.”

With his first pay check in his pocket, the first thing Charlie did when he got back into town was to head over to the music store that had sold him the drums on time, and pay off the note. After all, he was a working musician now.

Then again, maybe not. It seems that the Toronto club owner had called Ferguson’s agent shortly after their return to say, ‘Don’t ever call me again. That was the worst act I ever heard.’

Not exactly an endorsement.

And so the band folded, and with no prospects, and no money, Charlie was forced to call his mom and ask for a little financial help. And mom, being mom, sent him a little money to tide him over.

At the time, Charlie was living with a buddy of his, another future hall of famer named Kent Westberry. Westberry was a songwriter, and Charlie says there were always people coming in and out of Kent’s house to write songs.

One day, a woman named Mary John Wilkin was there, working on a tune, when, as Charlie recalls, Kent turned to him and said, ‘Hey, why don’t you get your harmonica and play along with this?’

“So I was playing along with this song and he said, ‘Man, this is really good for this song; I’m going to ask Mr. Denny if you can play on the session.’

“So I play on the demo session. A month later the phone rings, and it’s Jim Denny. And he says, ‘Hey listen, that song that you played with Kent? Chet heard that demo, and he called me and said, ‘I’m going to do that song with an unknown singer from Sweden named Ann-Margaret.’ [Charlie pauses to remind us that this was a couple of years before Margaret lit up the screen in .] ‘And he said, ‘Whoever played that harmonica on the demo, I want that person; and I want them to play exactly what they played on that demo.’

This was a good two years after Charlie had failed to impress Atkins with his rendition of Chuck Berry’s Johnny Be Good.

But this time around Jim Denny went with Charlie to the session, and started to introduce the harp player to the legendary producer. A glimmer of recognition came over Atkins’ face. “I know you” he said.

Charlie looked up sheepishly. “I auditioned for you.”

Atkins smiled. “You played Johnny Be Good. Man, I wish you had played the harmonica for me.”

“I thought I died and went to heaven” says Charlie. There was God, [Chet Atkins], there were the Nashville musicians, the Anita Kerr Singers, and twenty-year-old Ann-Margaret.

At the end of the session, the bass player, Bob Moore, came over to Charlie and said, ‘You free Friday?’ And hey I was free the rest of my life.” (Charlie laughs). “And he said. ‘You come back here on Friday. I’m doing a session with Roy Orbison.’ And we recorded a record called Candy Man, and when it hit the radio, my phone started ringing.

Candy Man: The record that launched McCoy’s career as a session musician…

“It was a huge hit” says Charlie, who had, in a few short months, seen his career do a complete turn-around. “I was working with the Nashville A-team, and the blessings continued.”

Sixty years later, McCoy is still at it. Looking back over his long career he says, “I probably played on more harmonica sessions than anyone on the planet.”

In the years that followed that first wave of success, Charlie worked his way around the harp, bass, drums and piano, while adding a bunch of new instruments to the list. A friend asked him if he could play electric bass, brushing away any of McCoy’s misgivings by saying, “It’s just like the bottom four strings of a guitar.” O─kay. Then Chet Atkins asked him if he’d play a few notes on the vibraphone. The vibraphone? “He said, “Go on out there; you can do it.’”

And he could.

And did.

“And I said, ‘Hey, this is fun. So a lot these instruments came after I was established as a studio player.

And the better he got, the hotter he got, backing the likes of Johnny Cash, George Jones, Paul Simon, the Steve Miller Band, Elvis Presley, and Bob Dylan. Six decades-worth of making music and memories. Like the first time he was called to do a session with “the King”.

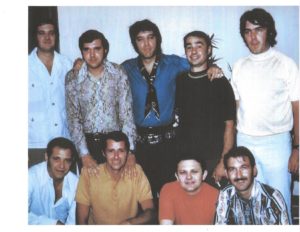

It was 1965. McCoy was just a young pup at the time, and not yet what you would call ‘first call’. He got his chance to play with Presley when the original recording date had to be changed, and, as Charlie put it, “the guys who usually recorded with Elvis were busy working on other sessions.

“So I was in the alternative band,” he says, describing the circumstances and first moments of that first Presley session as if directing the action of a play.

“He walks in the door. He doesn’t know anyone there, and he goes up to every musician, shakes their hand and says ‘Thanks for helping me’ – Yeah, we’re part of this team.’

The session was for the soundtrack to Harum Sacrum, and would be the first of seven Presley movie sound tracks he would record over the years. This, in addition to five of the king’s ‘regular’ albums.

Thinking back to those times, and Presley’s incredible fame, he says, “The studio was his safe place, away from the public, and surrounded by people he respected, good musicians and friends. Making music was his passion, so it was a great place to be with him.”

One of the things Charlie enjoyed during those sessions was getting to see the man who didn’t take himself so seriously. “He had a great sense of humor, says Charlie. “I once heard him ask one of the Jordanaires, “Hey, do I sound like those guys who imitate me?”

And it seemed like everyone in the music business was either imitating him, or trying to get their music in front of his producers. When a Texas song writer named Bob Johnston asked Charlie if he would make some demos with him, Charlie obliged. And while the demos didn’t immediately lead to Johnston placing a song with Presley, they led to him getting a job at Columbia Records and moving to New York.

At some point, the new New Yorker told McCoy that if he ever made it to the big apple to give him a call, and he’d get him a couple of Broadway tickets. When Charlie took him up on the offer, Johnston invited him to stop by the studio, saying, “I want you to meet Bob Dylan.”

And so he did, and ─he did. Said Dylan, “Hey why don’t you grab that other guitar and play along?”

The song was called Desolation Row from the album Highway 61 Revisited. “It was eleven minutes long, and consisted of just me and Dylan and an acoustic bass player. Aside from a few harmonica licks that Dylan played, I did all the background, and I was overwhelmed. We did two takes.”

Apparently Dylan was impressed enough with Charlie’s work to record his next album in Nashville. As soon as the date was set Johnston called his friend and told him to ‘call the guys,’ adding, “And by the way, Dylan didn’t want to go to Nashville. I was using you for bait.”

“So he came to town and we recorded Blond on Blond: the biggest record of his career, John Wesley Harding, and Nashville Skyline.”

And an aside: Just in case you were wondering, Bob Johnston would place six or seven songs in Elvis Presley movies, which is to say a chunk of a hunk, a hunk , a hunk of tunes.

But back to Charlie, and another pivotal moment. It happened at a Johnny Cash session, and was not only memorable because it was Cash, but because it led to one of the biggest records of McCoy’s career.

Remembering back to that day, Charlie says, “Johnny did a vocal version of Orange Blossom Special, which is normally a fiddle song. And Boots Randolph, who was an amazing sax player, was on the session. And he said, ‘Hey, Why don’t you guys figure out a solo on this?’

“So I got a couple of harmonicas and tried to emulate what a fiddle does, and they liked it. And after the session I thought, ‘I need to learn this song: it could be very cool for me.’

“I recorded it once at Cash’s tempo, and then again at a much faster tempo.” The second time around was the charm, and a major hit for a man who never set out to be “an artist”.

How would Charlie McCoy describe Charlie McCoy? “People ask me today, ‘Are you a singer?’, and I say, ‘No; I’m a harmonica player who sings.’

Says Charlie, “There are a lot of singers who play the harmonica.” And while he says he does sing on a lot of his albums, that’s not where his heart─or talent, lies.

Orange Blossom Special will be forever tied to Charlie McCoy, and he is heartened by the fact that so many harmonica players have taken it on. “I’ve heard it butchered a lot of times,” he says, “but it’s not easy, and I admire people who have the guts to try it.”

The song has been good to him, and, he says that when he plays a concert, it’s his closing song. Does he ever get tired of it? Not really. But he says that like a lot of the bluegrass tunes he plays, it requires a lot of speed, which is one of the reasons he says he loves playing ballads: tunes like I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry, and an instrumental version of Merle Haggard’s “Today I started Loving You Again”.

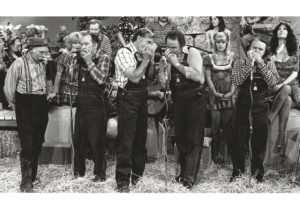

Aside from his work in the studio, on stage at the Grand Ole Opry and other concert venues, Charlie is also known for his time on Hee Haw, one of TV’s longest-running shows.

Explaining the format, he says, “It was Rowan Martin’s Laugh-In with country humor. The producers, Canadians Frank Peppiatt and John Aylesworth, were comedy writers, whose company “Yonge Street Productions” created and produced the show.”

McCoy notes that there is more than a little irony here, explaining that Yonge Street is one of the main streets in Canada, and the same street where the hotel where he played the drums for two weeks is located.

Cue the rim shot.

Hee Haw was originally set as a summer replacement on CBS, but when summer was over the network passed on putting it on the fall schedule. But Peppiatt and Aylesworth would not be deterred, and went about the process of putting it into syndication. Says Charlie, “Over twenty years later it’s still considered to be one of the biggest shows ever.”

Twenty-four season’s-worth of “big”. Charlie joined the show in season seven, became band leader in season eight, and music director in season nine, when the then current music director quit to Marry Tammy Wynett.

Charlie says that when he was first approached about doing the show, he wasn’t sure he had the time. “I thought, “I’m too busy to be on the show. But the band was only required to be there eight or nine days a month, and I said to myself, ‘I’ve got to figure out how to do this because this is so much fun.’ He would hang around for eighteen seasons, precisely because it was so much fun.

And Charlie says that having a good time doing what you love to do is what life’s all about.

And while he’s embraced the changes that have taken place over the years, both in the music and the way it’s recorded, he says that there comes a point where while technology has made recording more efficient, and offers up seemingly endless options, it also has its downside.

“I do a lot of internet work now,” he explains, “but it’s not the same as being in a room with other musicians and doing it all together.” Looking back at ‘the old days’ he says, “We didn’t have the technology; every-body played together. And if one musician messed up everybody had to do it again.

But it was a great way to learn this business when you had to do your best every time, and you didn’t get to go back and fix it. You had to be on your toes. There are so many brilliant musicians in Nashville, and when you get them together it’s magic. Today I know people that never have more than one person in the studio at a time. I think it’s sad.”

What’s not the least bit sad is an enviable career, and a life that’s taken him around the world, where he’s met, worked alongside of, and been honored by some of the most talented ─and finest people on the planet. And he’s not done yet.

Harmonica Jones, music by Charlie McCoy…

“I’ve been doing a good bit of songwriting’ he says, “─something I didn’t have time to do at the height of my career. Now I have the time, and I really love it.”

He also found the time to co-author his 2017 autobiography: Fifty Cents and a Box Top: the Creative Life of Nashville Session Musician Charlie McCoy, with Travis D. Stimeling sharing the writing credits.

It’s a good life, and getting better all the time, for which, he is most thankful. “I’m seventy-seven he says, and thank God, I’m in really good health, and I’m at the point in my life where I don’t need to do this anymore. But my heart and soul needs it. I still need it. And as long as I make the man in the mirror proud, I will do this.

Any advice for those who dream of being a ‘Nashville cat?’ “I don’t know what to tell you,” he says. “This town is so crowded with amazing musicians, and there are a lot of great players playing bars on Broadway for tips. They hope that important music people will come in and hear them. [But] Important music people don’t go downtown to Broadway very often.”

But Charlie does have some advice for those who just want to get better at their craft. “Listen to a lot of different players. Learn to play melodies; that will make you unique amount most players, and if you are on stage with a singer, less is more!”

To learn more about Charlie McCoy, his music, concerts, and that 2017 autobiography of his, go to www.charliemccoy.com.

Comments

Got something to say? Post a comment below.