Mark Hummel spent a good part of his life being the odd man out, which is to say, in the minority. And so it was that early on he was immersed in, and gained an appreciation for, the music and culture of races, places and cultures other than his own.

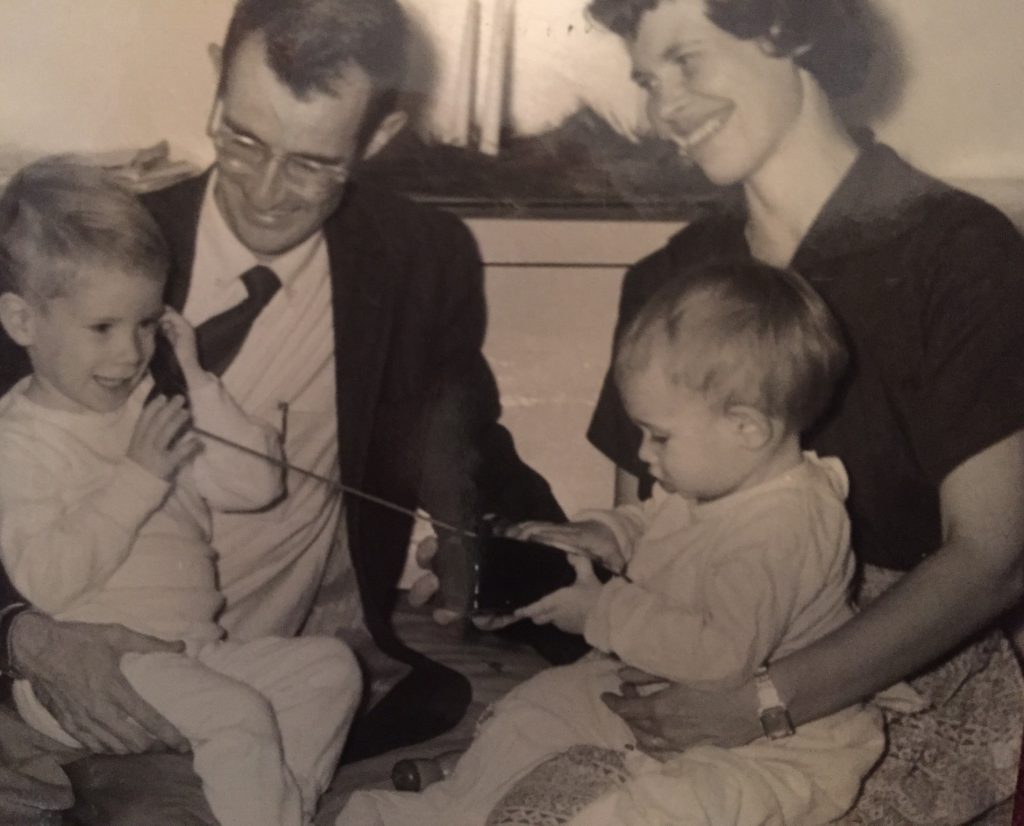

His parents met at Yale Divinity School in New Haven, Connecticut, marrying shortly after graduation. Mark, the first of their three boys, was born in December of 1955.

As with many ministers’ families, the Hummels moved where their father was needed most, often assigned to black and Mexican communities where they were the only, or one of the only, white families in their neighborhood.

Mark’s first memories are of life in Aliso Village, a housing project on the edge of downtown LA. From there, the family moved to east LA.

“I remember a lot about those times,” he says, many of which are tied to an array of babysitters who exposed the boys to soul music and the blues early on. Remembering those radio days, he recalls that, “You could hear Marvin Gaye and Jimmy Reed, R&B and the blues all mixed together.”

And the music just kept on coming. Notes Mark, “One babysitter drove us around in her Ford Fairlane. She had a 45 turntable set into the dashboard!”

With all that music going on, did Mark find his way to the harmonica at an early age? Not really. “I heard harmonica by the Beatles and Dylan,” he says, “but it wasn’t something I was drawn to at that time.”

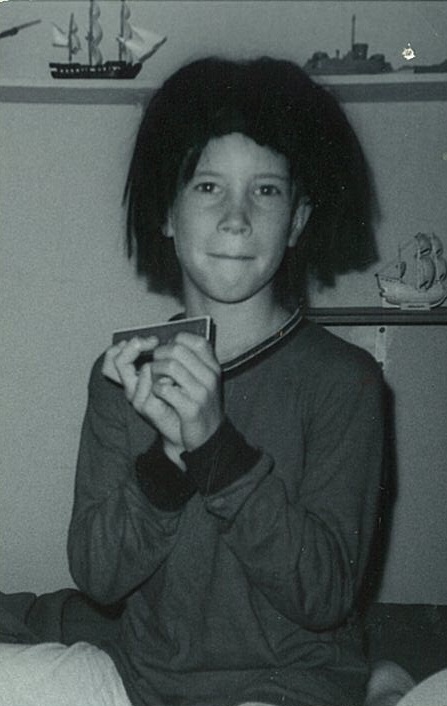

And yet, there was a moment when he was eight − call it a harbinger of things to come − when he literally held his future in his hands. “My parents gave me a Beatle wig,” he recalls, “and there’s a photo of me wearing it and blowing a harmonica in it.”

Cue the theme to The Twilight Zone.

Taking us from here to there, Mark moves the story on.

“When I was 11 or 12, we moved from east LA to another town called Monterey Park, where I spent sixth, seventh and eighth grade. I had a very different childhood than most white kids because where I was growing up I was in the minority. The projects were black, and east LA was all Mexican-American. I went to Sunday school with black kids and regular elementary school with Mexican-Americans. In fact, I was the only white kid in my class until the fifth grade. All that changed when we moved to Monterey Park, which was more of a mix of Mexican, Japanese and white kids.”

While every move had come with its own set of challenges, this one proved to be particularly difficult for Mark. “It was around that time that things started changing,” he says. “We were moving from a place I’d known to a place I didn’t know, and the rate of education was much quicker there.”

The difference was palpable. Whereas he had actually skipped a grade during his east LA years, he was now struggling to keep up with Monterey’s accelerated curriculum. And though he didn’t know it at the time, he was at a turning point in his life.

“When I was in sixth grade, I met a friend who gave me my first harp. He had a microphone and maybe a chromatic harmonica, and somehow I got those off of him.”

It was a friendship that would take Mark to a dark place. He says he was a bit of a ‘JV’ — short for ‘juvenile delinquent’ — and his friend only fueled the fire.

I was drinking and doing drugs by the time I was 13 or 14,” he says, recalling the day his friend introduced him to alcohol. “We got drunk together. I drank a pint of vodka and a pint of gin and got drunk as a skunk. Not long after that, I started smoking pot, and by the time I was in high school I was a full-blown f-up.”

Not exactly what you would expect from the son of a preacher man, but there it was. A year or so later, that same friend would take him on a ‘shopping trip’ to a music store, where they helped themselves to a handful of harmonicas.

In and out in just a minute.

Thankfully, that shoplifting caper would be both the beginning and the end of Mark’s life of crime, while drugs and alcohol would take on an increasingly bigger role.

The harmonica would be his saving grace.

“I was kind of lost before finding the harmonica,” he says, alluding to the fact that he was still having a hard time in school, and dealing with an escalating drug and alcohol problem. Music was an escape, and the blues harp was his vehicle. “Finding the harmonica was something I could put myself into that was out of that world.”

He says he accidentally discovered blues through “the hippy bands and blues-rock stuff” and the likes of Jefferson Airplane, Blue Cheer, Jimi Hendrix and Cream. “And there were songs by Big Brother and the Holding Company.”

It was a time of seeking out and digging in, with a curiosity that would not quit.

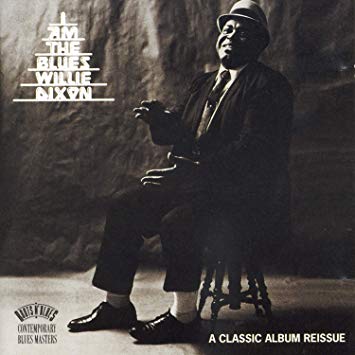

“I kept seeing song after song written by Albert King, B.B. King or McKinley Morganfield [aka Muddy Waters], and I found that Willie Dixon had written so many of the songs that rock groups had recorded. I was curious as to how all these things fit together. And that’s when I started getting into old time blues.”

It was a Dixon album that introduced Mark to what he refers to as “the older side of the blues.” His fabled Columbia release, I Am the Blues, would be the first blues album he ever bought. Notes Hummel, “It was the first record where I heard Big Walter, and it changed my life.

“I started borrowing records. A friend lent me a Brownie McGhee/Sonny Terry album, and that got my attention. And I went and saw the duo at a club called the Ash Grove.”

Years later, Mark would get to know Brownie, and appear on one of McGhee’s albums. But at this point in his life, he had to content himself with soaking up their sounds, be they recorded or live at various clubs, particularly the aforementioned Ash Grove, all this while learning as much as he could about the harmonica, and how to get the most out of it.

“I got Tony Glover’s blues harp book,” he recalls. “All the people in it were either dead or I was trying to go see. And there was a guy named Mark Dawson who was a couple grades older than I was. He was a harmonica player in bands, and played Paul Butterfield stuff. And I asked him if I could take lessons from him, and how much would it cost, and he said, ‘Just bring me over a six-pack of beer.’

“And so we sat in his garage and drank, and he played me the first Paul Butterfield album and second James Cotton record. And he lent them to me, and I was in awe.”

Dawson would also show Hummel how to bend notes. “And he showed me how to do vibrato with my throat and do a head shake, and those were all huge things in my playing.”

His next purchase would be a John Brim/Elmore James compilation with Little Walter. He played along with them, teaching himself a few tricks, and practicing for hours at a time. And the licks just kept on coming.

“I was on a mission to learn harmonica in general and blues harmonica in particular,” he says, ticking off a list of artists that were on his musical playlist. Among them: Magic Dick, Jay Geils and Lee Oskar. “I learned everything I could find on them,” he notes, adding, “I really went after the blues hard.”

While his parents weren’t exactly happy that their 14-year-old son was more interested in his music than his lessons, they were supportive. Mark credits his mom in particular with supporting his passion, literally going out of her way to drive him to and from the Ash Grove: no small gesture, in that it was a good hour’s drive each way.

“It was hard to find blues in Southern California,” recalls Hummel, the Ash Grove being perhaps the most receptive, but hardly a mainstay. “The audience was more of a folk crowd,” he explains. “Most of the people who tended to go there were white, but it was really the only venue that had touring Chicago blues people.”

When Mark wasn’t listening to music, he was making it, jamming with friends and thinking about the day he would graduate and escape the less-than-blues-friendly LA scene, to the far more progressive Berkeley area.

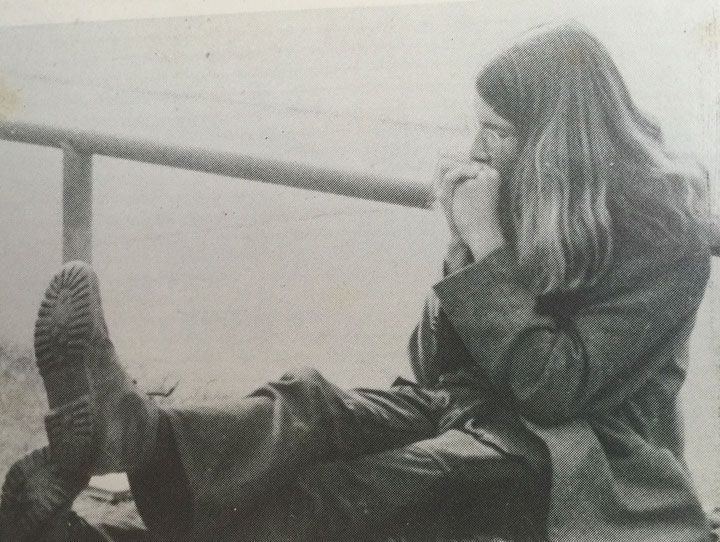

“I started hanging around with musicians. A lot of my friends were playing instruments at the time, and most were in bands. I felt uncoordinated on the guitar and gave up on it, but I had this natural affinity for the harmonica.”

And there was another plus: “There was a lot less competition on the harmonica. Everyone played it, but they played it badly. I put all my time into it; I was a fanatic. I was so focused on it that I would literally practice two to six hours a day. There’s a photo in my high school yearbook of me playing it on a lunch break. I think I was voted ‘Most likely to become a rock star.’” He laughs.

Prognostications aside, Mark says that performing on stage in front of a large group of his peers was a defining moment. “I didn’t sleep a wink the night before. I was making my debut.”

Hummel graduated in 1973 and followed up with a couple of years at Pasadena City College before moving to the Bay Area. “Bobby Bradford (who was a semi-famous trumpet player) was a teacher there, and he had a couple jazz classes − jazz improv and some other class − and those were really eye-opening for me.”

And then it was on to Berkeley, where Hummel met and moved in with a girl, and then left for a spell, hitchhiking around the country until he made enough money to return. And return he did, in late 1974. Alas the rekindled romance soon fizzled, and the wandering bluesman moved on, meeting some fellow musicians along the way.

“I met a conga drummer named Willie King, and he claimed that he used to drive Muddy Waters around when he was on the road. That was kind of a big thing: anything associated with blues. And through him I met a guitar player named Mike Lorenz, and we started playing on the street together. The Bay Area was a revelation to me. It was much more blues-friendly than LA.”

All he needed was a way into the clubs, which was, as they say, easier said than done. But one lucky day he met a fellow named Ron Thompson on the steps of Sproul Plaza, the hub of student activity at the University of California, Berkeley, where, notes Hummel, “all the student protests and anti-war protests started.

“Ron was playing on the steps, and he had a Dobro and was playing blues guitar with a slide guitar, and anything blues — I was going to scope it out.”

The two got to talking, with Thompson soon realizing that his new friend took his blues seriously. When Mark asked if there was a place where he might play the blues, Thompson showed him the ropes, taking him to clubs in the neighboring towns of Oakland and Richmond.

It was in Richmond that Mark got his big break, or at least his first gig, at a place called Thee Playboy Club.That’s not a typo. As Mark soon learned, this was not Hugh Heffner’s Playboy Club, but Thee Playboy Club. Big difference.

“It was a dumpy blues club in the middle of the ghetto. I was the only white face beside the bass player in the club. And so I approached him and asked, ‘You guys let anyone sit in?’”

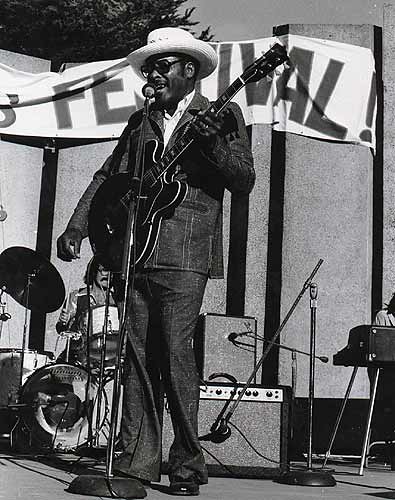

The answer was, “yes”, which led to his meeting musician, a cool cat named Cool Papa, and a singer named Charles Houff, who Mark would later work with.

“And so I sat in with them, and Cool Papa said, ‘You sound good. My harmonica player will be gone all next month; do you want to play Friday, Saturday and Sunday for a month?’

“I was stoked, and that was my first blues gig in the Bay Area.”

It was 1975.

“A couple of months later, another guy named Troyce Key called me up. He played blues and had a partnership in a band called the Rhythm Rockers.

Key and the Rhythm Rockers – I Got a New Car

“He wanted to learn how to play the harmonica, and so he said, ‘If you want to learn guitar we can trade,’ but all we did was yack on the phone about the blues.”

Key invited Hummel to check out a club in San Francisco called Minnie’s Can-Do. “At the time, I was going to every night club that had blues,” he says, “and so that was kind of a revelation.”

A couple years later, Troyce bought Eli’s Mile High Club in Oakland. Like Thee Playboy Club, Eli’s was an exclusively black venue. It was another step in the right direction, as, explains Mark, “I started meeting different musicians there, sitting in and sometimes getting hired by them, even going to their homes and recording things.”

“The next person I met was a guy named Boogie Jake. He was Little Walter’s cousin, and I was completely taken with that.” Mark played in Jake’s band and recorded with him for about a year, while continuing to play at various blues clubs and smaller rooms.

But while he was a working musician, his lifestyle was anything but working. Remembering those trying times he says, “I was still doing drugs and drinking and had a schizophrenic, drug-dealing prostitute girlfriend. I was a mess.”

And then in 1976, the phone rang.

“A guy named JJ Jones called me up. He was a guitar player, and he told me that he was starting a band with Johnny Waters. I had met Johnny at a jam at Eli’s two months before, and he had knocked me out.”

Jones asked Hummel if he had a rhythm section. He didn’t, but he put one together, and they became Eli’s house band. Together with Johnny and JJ, the group would be known as the Blues Survivors. Over time, members would come and go, but the band plays on to this day.

Mark Hummel and the Blues Survivors- Shake Dancer.

“JJ left the band within three months,” recalls Hummel, “and we filled his spot with a guy named Sonny Lane. Sonny was Johnny’s old friend, and they were more passionate about the kind of blues that I liked than anybody I had ever met.”

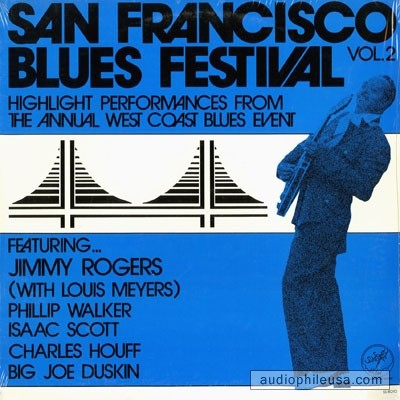

The group played pretty much non-stop around the Bay Area, including the San Francisco Blues Festival, but, after four years, the cracks began to show, and in 1982 they went their separate ways.

Mark kicked around for a couple of years, “did a few 45s”, and took his show on the road before returning to more familiar territory in northern California, but he knew that unless he got straight, his options were limited.

It was ‘my way or the highway’ time, and in this case, ‘my way’ led to a dead end. Mark stepped up to the plate, and came out swinging.

“I got straight in 1984 — right before going on the road,” he says. “I did it out of necessity because, in 1982, I was still drinking and thinking, ‘how am I going to do this if I’m doing this?’ because I was finally starting to get hangovers.”

“They were becoming a major issue. I was doing coke enough that my nose would start bleeding after the first line, and I thought, ‘I can’t play if I have a deviated septum.’”

How did he break free from his addictions?

“I did it with the help of the 12-Step Program. For me, getting sober was where I came to a crossroads, either one direction or the other. No more music because I wouldn’t be able to do it, because it would be too mentally and physically difficult.”

“So I kind of knew what I had to do, and my last year doing it was pretty miserable. When it got to a point where I was looking forward more to the break than being on stage, that worried me.”

And so, in 1984, Mark Hummel made the commitment that would change his life.

Some 35 years later, he laments at how many of his friends and fellow musicians lost the battle to face their addictions.

“Three of the guys in the original band are dead: Johnny, Sonny and Lex (the band’s bass player) all died within three years of my being on the road. By 1987 they were all gone.”

Newly sober, Mark was ready to put the show on the road, putting together a new edition of the old band, and sending out demos to various venues across the United States. Before long, the group was traveling to New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Washington, Arizona and Montana. And, while it was rewarding, during those cold winter days it was no picnic.

“We went through some real blizzards, and it was hard because I had a crappy van and the heat would go out, and I was ripped off by club owners and whatever, but it was an adventure to me. I loved traveling. I had put out an album and it had done well for me. It was getting air play in the Bay Area on a major station where they actually played local people. And we went to Europe a year or two after that and started going over on a regular basis, which was exciting.”

Mark Hummel, Sue Foley and the band: How Long Must I Wait.

“So I was on the road — on average — about half a year. And in 1989 I worked with a Canadian artist named Sue Foley. It gave me a break from my own band. We were on the road for 10 months, and that cured me of wanting to be out that much.”

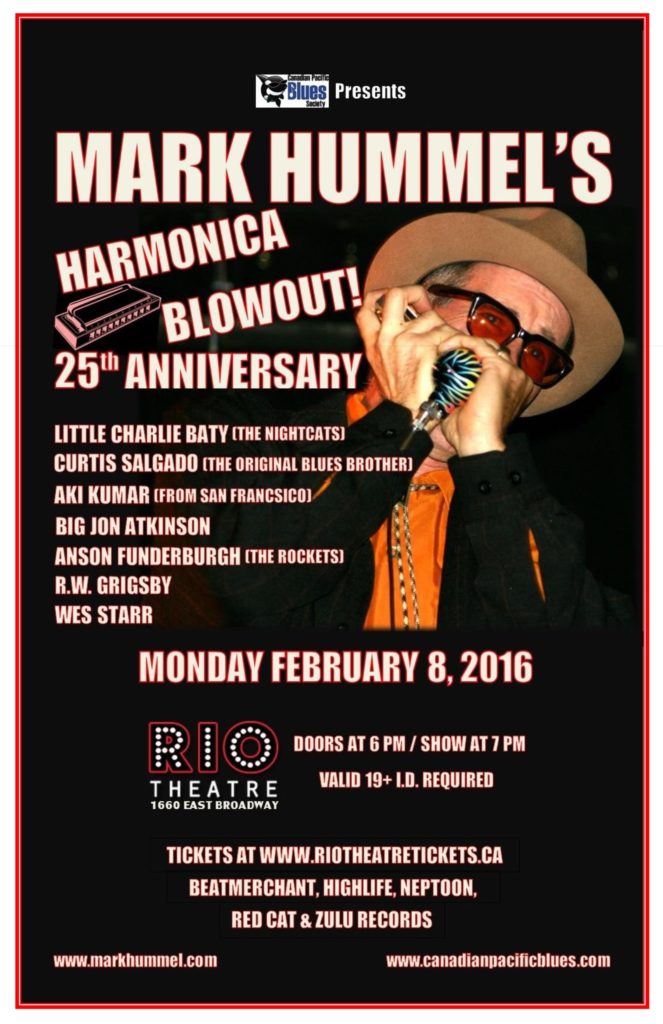

And so he turned his attention to something new — something closer to home, something that would bring the best of the blues to a whole new audience. It took a couple of years to put it together, but when The Blues Harmonica Blowout made its debut in 1991, it rocked everybody’s socks off.

How did it come about?

“There was a guy named Tom Mazzolini who did the Battle of the Blues Harps, but by then he was doing them less and less. He had done the San Francisco Blues Festival for many years and put his eggs in that basket. And so, when he slowed down on the Battle of the Blues Harps, I picked it up and brought it to the east bay (Berkley) whereas he had done his in San Francisco.”

“The first blowout was done on a far smaller scale than Mazzolini’s. I did it on that first Martin Luther King Sunday, and we attracted 150 to 200 people. Rick Estrin, who was an old friend of mine, was the headliner, and I had Dave Earl and Doug Jay, and my band played behind everybody. And that was the show.”

As Mark tells it, after that first Blowout, the owner of the venue said, “That really went well; let’s do this every year”, and so he did, turning the shows into traveling tours that grew from one to two days, then three, then five, then 10, to as much as two weeks, mostly on the West Coast, with bigger and bigger names signing on as he went.

“I was having everybody from William Clark to Norton Buffalo in the mid– eighties; by late the late eighties I had Billy Boy Arnold, Carrie Bell and Kim Wilson.

And, by the early 2000s, I had Charlie Musselwhite and James Cotton and eventually John Mayall, John Hammond, Snooky Pryor, Lee Oskar and Magic Dick.”

By 2006, the tour was making its way to the East Coast, Midwest and beyond, hitting the clubs and summer festivals and even going overseas.

Magic Dick – I Got to Find My Baby, recorded live at the Blues Harmonica Blowout, October 21, 2008.

Magical times that continue to this day.

Off-tour, Mark Hummel and the Blues Survivors were in the studio, and there were Blowout CDs featuring a number of different artists as well.

One album in particular — 2014’s Remembering Little Walter on Blind Pig Records — would win him a Grammy nomination for Best Blues CD, as well as two Blues Music Awards: Album of the Year, and Best Traditional Blues Album.

Mark Hummel plays I Got to Go from his Grammy-nominated Remembering Little Walter album.

2012 was also the year Mark put two and two together, the “two” being guitarists Little Charlie Baty and Anson Funderburgh, both of whom were semi-retired. The two men had known each other but never worked together. Hummel thought it was time to change that scenario, bringing them together as part of an ensemble, where he would play harp and perform the vocals, with bass and drums rounding out the group. He pitched the idea to the two, and they said they would try it, which resulted in the first Golden State Lone Star Blues Revue in 2012.

The name came from the fact that Mark, Charlie and bass player R.W. were living in California, while Anson and drummer Wes Starr were living in Texas at the time.

Golden State Lone Star Blues Revue – Walking with Mr. Lee.

“It really became my main focus,” says Hummel. “I liked having a group that was more guitar-oriented because times had changed and you needed that guitar factor to get the attention. And three guitars in a band instead of one did that.”

The Golden State Lone Star Blues Revue with Mark Hummel , Anson Funderburgh, Mike Keller, Wes Starr and R.W. Grisby/Shake for Me.

Hummel’s 2014 album The Hustle is Really On featured the group, along with Kid Andersen, Doug James, June Core and Sid Morris, and claimed the number two spot on the Living Blues Radio charts for several months.

The group continued to tour in one form or another, with Baty leaving and Mike Keller signing on in 2016, which was another pivotal year in Mark Hummel’s life.

The Golden State Lone Star Blues Revue was in high gear, with Mark and the boys spending some 160 days of what Mark refers to as “hard-core road work.” He had been on that path for more than three decades, and the unrelenting grind had taken its toll both on and off the road.

“I had been through a lot of stuff,” he says. “I had a daughter, and I suffered through a divorce with her mom, and they had moved out of state when she was five.”

The separation had hit him hard, and there would be heart-related issues of a different kind in 2016.

“I had just gotten off the road,” he says, “and I was walking my dog, which I did two or three times a day, and my chest would burn.

“By the tenth day, l was walking into the kitchen and my chest burned again. And I went to doctor and he said, ‘Your blood pressure is high; your cholesterol is high; you should be on blood thinners and blood pressure pills.’ And he prescribed them.

“Later, I felt a tightening in my wrist, and I knew something was off. So I went to the emergency room and they ended up keeping me. And that’s when I had a stent put in.”

Hummel had suffered a minor heart attack.

Having had the time to sort it all out, he says, “I think it was related to the pitfalls of living on the road. It’s hard to eat well, and there’s a lack of exercise because you’re traveling in the van six to eight hours a day.

Cabin fever starts setting in, and so after 32 years of that, it took its toll, and I kind of made up my mind to travel a bit less.”

“Less” turned out to be nearly a third of the year. Two stents later, Mark was finally getting the message:

Slow down. Take it easy. And so he did.

“My mom died at the end of 2017, and she left me and my brothers some money, so I didn’t have to worry about having to be on the road. And so I stayed home, just doing one long five-week tour and some 10-day tours.”

Mark Hummel and the Ultimate Harmonica Blowout – Things Ain’t What They Used to Be.

Looking back over a career that has spanned more than 45 years, Mark Hummel can rightly say that he toured, performed alongside of and/or recorded with the best of the best, headliners like Charles Brown and Charlie Musselwhite, Huey Lewis and Howard Levy, Billy Boy Arnold and Carey Bell, Eddie Taylor and Jimmy Rogers, and all of the gifted musicians who have made Mark’s music all the sweeter, among them, Anson Funderburgh, Wes Starr, R.W. Grigsby and Mike Keller, who, along with Mark, would garner not one but two Blues Music Award nominations: for both Band of the Year and Traditional Blues Album of the Year.

Today, Hummel is enjoying life both on and off the road. “I met my current wife in 1995,” he says. “She had two daughters, and our daughters became good friends. So I’ve been really lucky with my home life, and I’m a grandpa! I’ve got two grandkids and we’re very close.”

Which is to say that life is good for Mark Hummel. He’s still performing and recording, racking up those nominations and awards while knowing the joy that comes from being with family and friends. Over the course of his career, he has seen the music business change rather dramatically, posing a host of challenges for both established and upcoming road warriors.

“I have a lot of tenacity,” he says. “Say what you will about me, I don’t give up easy. In 1984, I decided that if I was going to sell records, I was going to do it nationally. But what I found was that if you didn’t go on the road, you risked losing your audience. If you wanted to get your name out there that’s what you had to do.

“The whole scene has changed so dramatically since then. There’s such a stark difference. People are watching YouTube videos instead of going into a night club to see you, and CDs are on the way out, which is dangerous for touring artists because CDs and LPs help keep us afloat. So it has a huge effect on touring musicians.”

Add these to a whole list of things that Mark says have made life on the road more difficult. Another reason why, these days, he’s focusing on recording. “I’ve always tried to vary the albums I’ve put out” he says, pointing to his all-instrumental release, Harpbreaker, a compilation of new and unreleased recordings.

Cristo Redentor for Hummel’s Harpbreaker album, cover photo by Bob Hakins.

“I had some material I’d recorded in 2007 that I really wanted to get out there, and while it didn’t fit on a blues record, I could put it and a variety of things on an instrumental album: from country blues to electric Chicago blues and jazz numbers.”

Chuckaluck, another great cut from Harpbreaker.

An upcoming release features the Deep Basement Shakers, a jug band that consists of piano, washboard, suitcase kick-drum, guitar and harmonica. Add to that “an old time blues singer” named Joe Beard. “It’s essentially pre-war blues stuff,” says Hummel, “a different approach,” though he’s quick to add “I’ve been playing some of this old-style country blues stuff since the beginning when I was with Brownie McGhee.”

Asked if he had any tips he’d like to pass on to our readers, he says, “The one thing I have felt all along my musical career is that if you take your focus off the music itself, it’ll be your downfall. You have to be totally committed to something you want to do, and something you love. You read about musicians all the time who say, ‘I came back to this music because it’s what got me into it in the first place’ ”.

“There was a time where I was much more focused on entertainment: buying a wireless mic, jumping on the bar, taking the audience out into the street, getting on my knees, rolling on my back and kicking up a storm. But there’s a certain point when an artist has to change to suit himself.”

“A friend who was kind of my mentor back in Berkeley once told me ‘There are two kinds of musicians: entertainers are like Chuck Berry, who have a need to make the audience love them, and musicians who love the music, like Mose Allison.’ Entertainers tend to be more insecure. Real musicians are not coming from a place of insecurity but depth. In his own way, Chuck Berry was extremely deep, but the show business aspect eventually overshadowed it, and his shows suffered because of it down the road.”

“You have to love what it is you do at the expense of pain, money and recognition. People who lose sight of the music and chase after fame are forgotten.”

“Follow your heart.”

For more information on Mark Hummel and his music, tour dates, Blowouts and other upcoming appearances and releases go to Markhummel.com. And be sure to check out his book, Big Road Blues: 12 bars on I-80. It’s available through Amazon.com and other retail outlets.

Comments

Got something to say? Post a comment below.