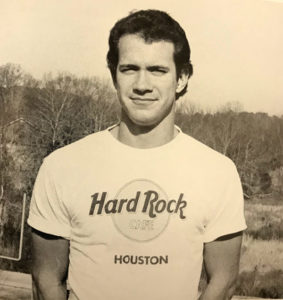

Scott Albert Johnson has been around. By the time he was thirty, he had lived in Missouri, Mississippi, Alabama, Massachusetts, New York, California and the District of Columbia. But it is Mississippi that he calls home; it’s where roots were grown, and hearts were won. And it would be Mississippi that called to him, and to which he would return.

Unlike many harmonica players, Johnson didn’t pick up the harp until he was in his early twenties, his musical education beginning sometime between the second and third grade, when, like many children his age, he took Suzuki violin lessons.

Scott stayed with the violin for a few years but, by his own admission, he wasn’t very good at it, eventually setting it aside. “Many people were happy about that,” he laughs, adding that, despite that fact, those lessons served him well, providing a framework for later musical endeavors.

As time went on, Scott found that he had a pretty good voice, joined the school choir, and used his vocal talents to win a series of leading roles in various middle school plays. And the harmonica? It was but a glimmer in his teenage eyes. “I was a singer and a bass player long before I was a harmonica player,” says Johnson.

The bass – a gift from a ninth grade pal – had barely changed hands when another friend approached Scott about playing a gig the following Friday.

“I said, ‘I just got it’,” he recalls. “I don’t know how to play it.”

“Don’t worry,” said his friend, “I’ll show you a few things.” And so he did. Enough to get him started.

Johnson would go on to join the school’s jazz ensemble and make music with the same core group on the side. It was a time for learning, experimenting and doing some serious listening to everything from Duke Ellington to Jimi Hendrix. “I had friends who had big brothers,” says Johnson, “and they got their music from those older siblings. I hung out at their houses and we would listen to the music and jam.”

It was an eclectic mix that included 1960s rock, a bit of jazz, and seventies and eighties pop. “I was a serious Peter Gabriel fan,” he recalls, noting that his last album (Going Somewhere) features a cover of I Don’t Remember, one of Gabriel’s tunes. Other early influences included Led Zeppelin, Randy Newman, and Van Morrison.

That music would become a part of his life songbook, “swirling around in one big gumbo,” a dash of St. Louis blues here, a pinch of Hattiesburg, Mississippi soul there.

“They’re all a part of the mix,” he explains, “affecting me in ways I don’t know.” But then Johnson contends that all song writers and musicians are impacted by everything they experience, musical and otherwise.

As for attaching a label or genre on a musician, Johnson says, not so fast. “In the end, it’s all music,” he explains. “I’m a firm believer that the genres laid on one artist or another are just estimates, marketing more than anything else.” Which is why he hesitates to put his own music in one category or another.

“There are 12 tones in the western chromatic scale,” he says, “and those 12 tones can be put together in different ways.” In other words, at the end of the day, “it’s all music.”

Though Johnson would eventually take that music and run with it, the idea of becoming a professional musician wasn’t even something he considered after high school.

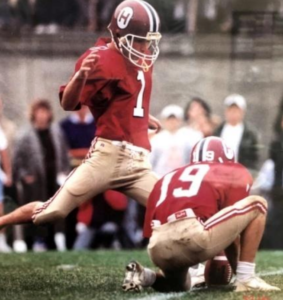

He chose a more traditional path, heading to Cambridge, Massachusetts and Harvard University, where he would earn a degree in political science.

As you’d expect, his studies took up the bulk of his time there, but he did kick for the school’s football team and play bass with a couple of bands.

He also took up the harmonica.

He says that, at the time, playing the harp wasn’t something he took very seriously. “I just fooled around with it,” he says. But there were hints of things to come, like the night before a major exam on Greek heroes, when, instead of hitting the books as his roommate did, he was ─ shall we say ─ otherwise engaged.

“I was a notorious procrastinator,” he explains, “while he was rather compulsive. When he heard this noise coming from my room, he opened the door and found me sitting on my bed with the harmonica, a book, and an instructional cassette tape.” As Scott recalls, the conversation went something like this:

Roommate: “What the hell are you doing?”

Johnson: “I’m working on this. Just a second.”

Roommate: “We have an exam in five hours!”

Johnson: “But this is really important.”

Looking back at that moment in time, Johnson says, “I was actually right.” No joke, the harmonica having played a far more important role in his life than all of the Greek heroes combined.

Sorry Plato.

By the time Scott Albert Johnson got his degree, he had a basic feel for and understanding of the diatonic, but was still unclear as to what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. But, after four years of immersing himself in governmental issues, Washington seemed like a logical place to land. DC was, after all, where the ‘action’ was, and Hillary Clinton’s Health Care Reform effort was in full swing.

He landed a job at the White House, where, he says, he was more of a helper than game-changer, and after a year of answering phones, he was ready to move on and do something that spoke to his creative side.

Like being a working musician? Not quite. Not yet. He would first make his way to New York City, where he would earn a Master’s degree at Columbia School of Journalism. Despite the detour, Johnson says that, even though he wasn’t “doing music” at that point, it remained in his heart.

After graduating, Scott worked at a non-profit, where he met a fellow musician who, like Johnson, was interested in working up a few songs and playing a party or two along the way. That lead to Scott’s pushing the envelope a bit, with the idea of learning to play “a couple of songs on the harmonica.”

“So, I bought a set of cheap harmonicas, and I became totally obsessed really quickly. I thought ‘I’m just going to throw myself into this’. But I quickly realized that I had an aptitude for it.” It was a “natural ability” that surpassed anything he had experienced with the violin or bass.

With only a rudimentary knowledge to spur him on, he turned to the Internet for help, picking up what he could from those who knew more than he did about playing cross harp and straight harp.

“I think I figured out the whole idea of position on my own through trial and error,” he says, adding, “I feel like most diatonic players are either trying to play in a traditional blues style and be the next Little Walter, or leaning towards the Neil Young style of playing rudimentary blow-in/draw-out patterns that are very melodic but aren’t very specific, complicated or sophisticated.”

Scott says that rather than heading down either of those roads, he just wanted to play whatever he heard, no matter the instrument or whether it was in a major or minor key.

It was an energizing time. He added writing to his musical arsenal and, in doing so, became a triple threat. “And the more I started playing actual gigs, the more I thought, ‘This is actually the outlet for my creativity that I’ve been searching for. Maybe this is the way to go’.”

And there was another question, which was not only which way to go, but where? The answer lay in the things he did know: “I knew I wanted to be closer to my family, and be where I could really start moving forward music-wise. And I felt that moving back to Jackson, Mississippi was a good first step.”

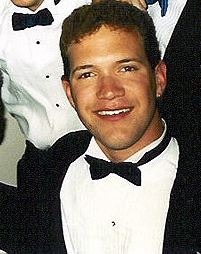

And so it was that, in early 2003, Scott Albert Johnson moved back to the place he called home. A month later, he started dating the woman who would eventually become his wife. By 2005, they had married and had their first of three children. By 2007, he had recorded his first album. With Jackson, Mississippi as his base, he found that New Orleans was an easy drive away, with plenty of opportunities to perform. An occasional East Coast tour and a European gig added to the mix.

Before long, he was maintaining a heavy recording and performing schedule, averaging 175 gigs a year, while holding down a nine-to-five job. And he’s never looked back.

All these years later, he remains dedicated to the harmonica, and the people, places and music that embrace it. “That dedication has never stopped,” he says. “There’s a connection between the culture, the music and everyday life that is more tactile. It’s present all around you. And I think there’s a little more headspace taking what’s around you and connecting it to the music you make.”

As for those pesky labels, Johnson says, “I wouldn’t call myself a Southern artist – but I do think (to quote Mark Twain) that you should write what you know about, and that seems to come through.”

Given some of his musical choices, we asked if he had ever considered playing or switching to the chromatic. “I messed around with it,” he says, “but I am an overblow player. The diatonic has been part of my style for years, and I can’t extricate that from my playing. It comes easily to me. I can play the phrases I want on the diatonic and express the individual notes or phrases. I like the diatonic.”

Not that he hasn’t been influenced by the instrument and phrasing of the likes of William Galison and Toots Thielemans. “I find it very appealing,” he says, “and I feel like I do a lot of that in my playing.”

Read between the lines and you come to realize that, for Scott Albert Johnson, there are no restrictions other than those you place upon yourself. He sets no limits on what kind of music he can or should write, sing, play, or draw from.

Asked if he had any advice for those harp players trying to find their own musical niche, he replies, “Don’t just listen to harmonica players; it’s self-limiting. Listen to all kinds of instruments and music. Listen to singers. Listen to their phrasing. You’ve got to be open to everything.”

His other piece of advice is perhaps hardest to follow: “Try really hard not to play the same licks or combinations of notes you’ve fallen back on.” It is, in fact, something he struggles with constantly. “In blues there are some licks that are so totally identifiable, and it’s so easy to fall back on them. But if you think that way, you won’t come up with something new rather than something someone else has already done.

“And so I would challenge players to try and get through an entire song without playing something they’ve played before. I have to remind myself of this, and it’s a constant challenge.”

You need only listen to Johnson’s performance of It’s a Wonderful World at a recent Boston Pops concert, where he was a guest artist, to see that such diligence pays off. Speaking of that performance he says, “There were plenty of overblows playing 2nd and 12th position, but there was never a moment where I played a lick, or did something that I had thought out before.”

Scott notes that while he believes that you should stick to the words and melody of a song, or something close to them, the rest of the arrangement is what you make it. “I stay close to the spirit of the tune,” he says. “That’s what’s important.”

Scott Albert Johnson is living proof that spontaneity begets creativity. To learn more about the man and his music go to scottalbertjohnson.com.

Comments

Got something to say? Post a comment below.